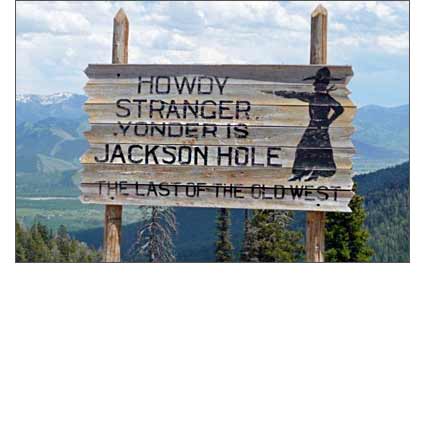

THE LAST OF THE OLD WEST: A Cautionary Tale…

This is the story of the part played by the author in the utter transformation of a remote, beautiful and largely unspoiled Rocky Mountain ranching valley into a high-voltage, world-renowned mega-resort named 2014’s Richest County in America.

THE LAST OF THE OLD WEST: A Cautionary Tale

For thirty-four years, pretty much the middle half of his life, the author designed houses for other people. He was a “small-town architect.” That’s in quotes because, for openers, there’s really no such thing as a small-town architect. Nobody in a small town thinks they need an architect, or if they do, they can’t afford one. If their builder wants plans at all, he’s either got a kid in the back room who did OK in high school drafting class or he’ll hire the guy down at the lumber yard with the same credentials.

Then, too, the place where he worked, although certainly small by almost any standard, was anything but your garden-variety small-town. His tenure there spanned the exact time during which it underwent a total transformation from the “Last of the Old West” to the “Best of the New.” It was and still is quite a place.

This is the story of the rise, and some would say fall, of Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

Take a look inside this publication

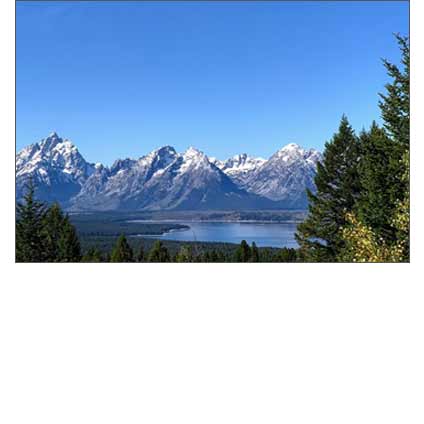

Teton Range and Jackson Lake viewed from Togwotee Pass

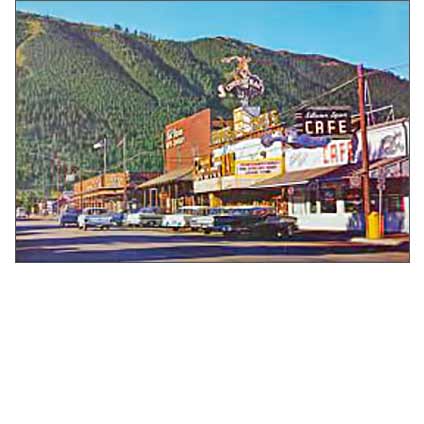

Teton Range and Jackson Lake viewed from Togwotee Pass Town of Jackson, WY ca. 1967

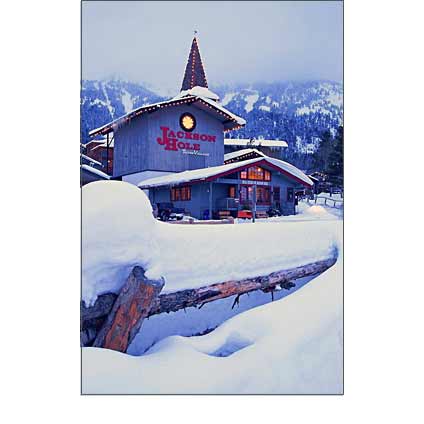

Town of Jackson, WY ca. 1967 Original Tram Base Station at Teton Village

Original Tram Base Station at Teton Village Town of Jackson, WY ca. 2017

Town of Jackson, WY ca. 2017 Author's $13,000 self-built, earth-bermed, 3-bedroom house ca. 1968

Author's $13,000 self-built, earth-bermed, 3-bedroom house ca. 1968 High Country West mountaineering expedition, Wind River Range, ca. 1970

High Country West mountaineering expedition, Wind River Range, ca. 1970 Wilson, WY Troop 40 BSA @ Summit of Grand Teton, 1975

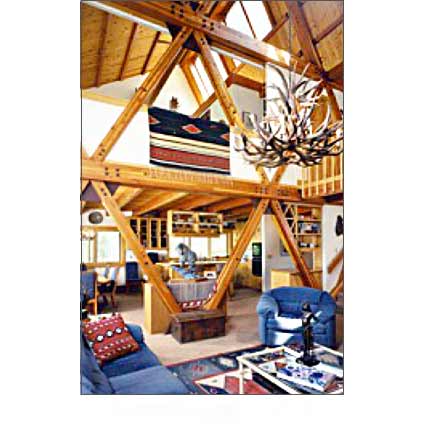

Wilson, WY Troop 40 BSA @ Summit of Grand Teton, 1975 Trussed "treehouse" interior, 1975

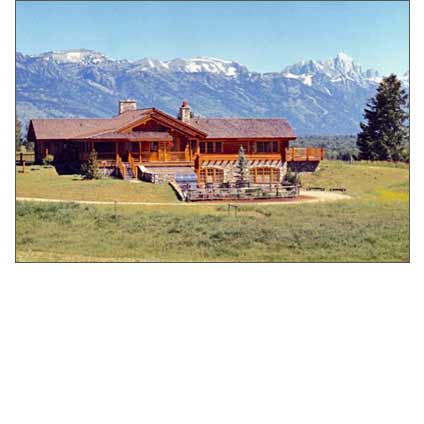

Trussed "treehouse" interior, 1975 Log ranch house, 1987

Log ranch house, 1987 Presentation drawing, Skyline Ranch residence, 1978

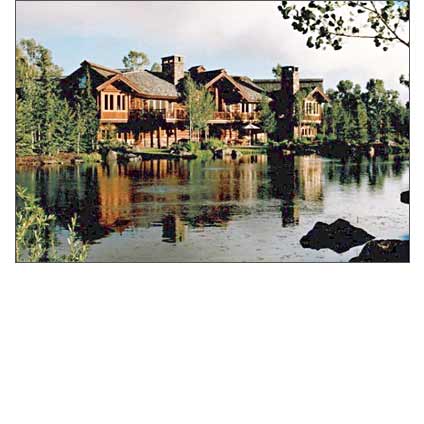

Presentation drawing, Skyline Ranch residence, 1978 CEO part-time "getaway" complete with artificial trout pond, 1990

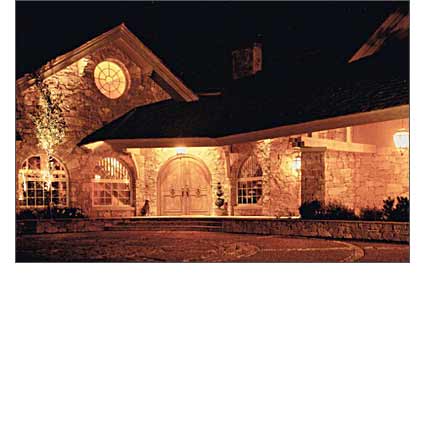

CEO part-time "getaway" complete with artificial trout pond, 1990 Stone "manor house," Teton Pines gated community, 1993

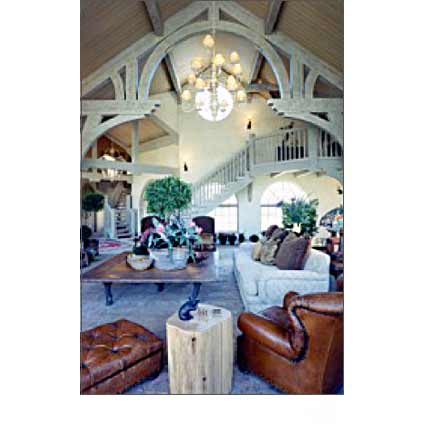

Stone "manor house," Teton Pines gated community, 1993 English "hammer beam" trusses @ "manor house" interior

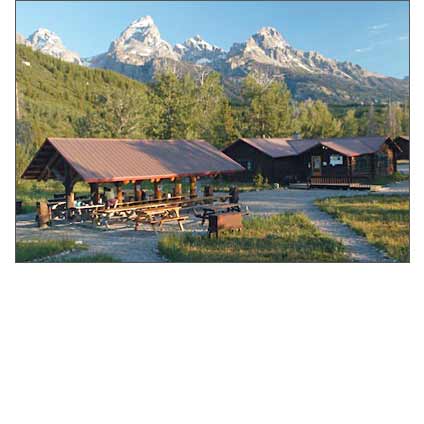

English "hammer beam" trusses @ "manor house" interior Cooking shelter @ American Alpine Club's "climber's ranch," Grand Teton National Park

Cooking shelter @ American Alpine Club's "climber's ranch," Grand Teton National Park Welcome sign atop Togwotee Pass

Welcome sign atop Togwotee Pass

Excerpt

The 80s and 90s were heady times for a small-town architect in Jackson Hole. The wealthy were pouring in, many looking for expressions of their success with which to dazzle their out-of-town, cocktail party and dinner guests. The answer I’d given to Mike Sellette that big money doesn’t necessarily mean great architecture was proving to be true. As the houses became larger and more opulent, many became showplaces rather than homes. I tried to avoid it in my own work, but in some of the monstrosities being built it was hard to find a single comfortable room unless you were entertaining thirty friends. Even the log construction I’d thought so ‘honest’ was being corrupted by the addition of hidden steel to accomplish structural feats not possible with even the largest logs. Contrarily, some macho clients demanded giant 24″ wall logs for the most modest structures, turning whole projects into architectural cartoons. None of this posturing had anything to do with architecture. It was all just expensive stagecraft.

Toward the end of the 90s, a number of other factors came together suggesting that it might be time to hang up my T-square. I’d been at it for thirty years and hours hunched over a drafting table were losing the appeal they’d once had. Computer Assisted Drafting, or CAD, was fast coming online anyway, changing the entire process of doing the drawings I had so enjoyed crafting by hand. My son Chris, now working full time, ordered a new program called Archicad 1.0 that revolutionized even the architectural design process. It was aimed specifically at architects and automatically created construction documents based on an ongoing, 3- dimensional screen model of the evolving design. He quickly became a digital wizard and continues using it today, but at level 23.0, leading an expanded and vibrant D/A more technologically sophisticated than anything I’d ever imagined. Before turning the firm over to him, I’d made a half-hearted attempt to learn the futuristic ropes, but kept falling back on my old, familiar ways. Drawing lines with a pencil was not only easier, but more satisfying to a dinosaur like me than learning, and then having to remember all the tricks of doing it electronically.

Dealing with the increasingly Byzantine county permitting process, for which I had been an early advocate was also starting to wear on me. Most of my time, it seemed, went into accommodating my designs to a myriad of ever-changing code requirements, plan reviewers and site inspectors. It was no fun anymore. A flap that arose with one of my wealthy clients about this time illustrates the point. CEO of one of Hollywood’s major film studios, he and his wife asked me to design a plush guest house for their many important visitors. The county rules limited the square footage of such structures to “ten percent of the area of the principle residence,” in this case ten thousand square feet. With this in mind, I came up with a handsome little one thousand square-foot cottage, did all the drawings and submitted them to the Planning Department. Shortly thereafter, the County Planner called to reject my submission on the grounds that it was “too big.” I protested that it was precisely ten percent of the main house. “Did you include the garage?” she asked. “Of course,” I said, there being no language in the rule suggesting otherwise. “We exclude garage areas,” she replied. When I noted no such exclusion in the written text, she admitted that it was just an “office policy!” How the hell was I supposed to know that? I solved the problem, but it was a stressful negotiation.

The final blow came in the most unlikely of places, Easter Island. Nancy and I were participating in a NOVA TV production there, dealing with methods for moving and erecting the giant stone statues, called moai, for which the island is famous. At one point during the filming, an islander was injured and needed medical care.

Re-erected Easter Island moai, Nancy at lower right

Not being on-camera just then, I offered to take him to the tiny medical clinic then the only hospital for thousands of kilometers in any direction. Nancy and I loaded him into the Suzuki Samurai we’d been loaned during the shoot and sped off across the tiny island. Our patient wasn’t badly hurt and received the first aid treatment and stiches he needed from the clinic’s lone doctor and nurse, using just the few basic supplies available. What if he’d been near mortally wounded or seriously ill? we wondered. What then? Without a plane ticket to Tahiti or Santiago Chile, both about 2500 air miles away, he’d be out of luck. It struck me that for the money my clients routinely spent just furnishing their second, third and sometimes fourth homes in Jackson Hole, the Rapanui islanders could have had a decent, well equipped hospital. Hard to imagine, I know, but for the first time in my career it dawned on me that what I was doing was not only less fun than it used to be, but a little bit crazy and maybe even shameful.