FORGOTTEN VILCABAMBA: Final Stronghold of the Incas

One man’s quest becomes an obsession to solve the mysteries surrounding Vilcabamba, the Incan Empire’s final stronghold, in the jungles of Peru

Forgotten Vilcabamba: Final Stronghold of the Incas

An important addition to the annals of archaeological exploration in the high Andes of Peru by architect/explorer Vincent R. Lee describing lost Vilcabamba, the once-powerful Incas’ mysterious redoubt in the jungles of the Upper Amazon. Woven together are the region’s bloody history in the aftermath of the Spanish Conquest, the saga of intrepid early efforts to unlock Vilcabamba’s secrets three centuries later and the author’s long but successful campaign to bring the hidden ruins of the Incas’ long-forgotten final stronghold back to life.

A modern-day scientific adventure set against a fascinating historical backdrop, “Forgotten Vilcabamba” has 515 pages, including 48 color plates, 60 pages of maps and drawings and a 65 page “Guide to Inca Vilcabamba,” an invaluable key to this newly popular trekker’s alternative to the badly over-crowded Inca Trail and Machu Picchu. For more information about Vince Lee and his explorations in Vilcabamba, read Kim MacQuarrie’s new book, ‘The Last Days of the Incas,’ available at lastdaysoftheincas.com.

University libraries, archaeologists, trekkers and armchair adventurers throughout the U.S., Canada, Europe and Latin America have been universal in their praise of Forgotten Vilcabamba.

Take a look inside this publication

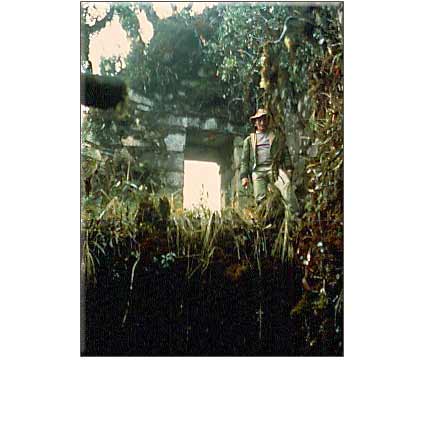

The Incahuasi at Puncuyoc, Peru, as first seen by the Sixpac Manco Expedition II in 1984

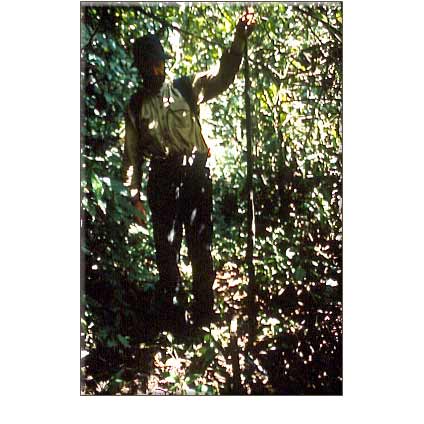

The Incahuasi at Puncuyoc, Peru, as first seen by the Sixpac Manco Expedition II in 1984 José Salas Cobos clearing the Incahuasi in 1984

José Salas Cobos clearing the Incahuasi in 1984 Paul Burghard inside the two-story Incahuasi ("Inca House") in 1984

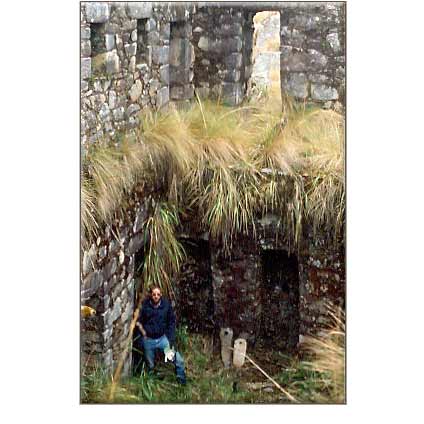

Paul Burghard inside the two-story Incahuasi ("Inca House") in 1984 The overgrown ruins of Vitcos atop the hill of Rosaspata and overlooking the village of Puquiura, Vilcabamba, Peru

The overgrown ruins of Vitcos atop the hill of Rosaspata and overlooking the village of Puquiura, Vilcabamba, Peru Inca terraces at Vitcos, Vilcabamba, Peru

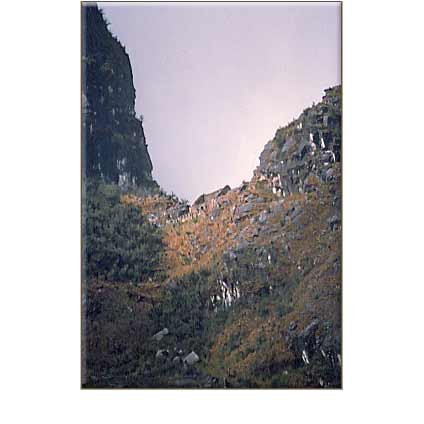

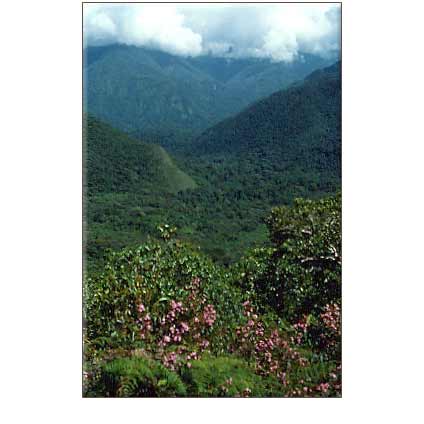

Inca terraces at Vitcos, Vilcabamba, Peru Pico Iccma Ccolla overlooking the valley of Espíritu Pampa ("The Plain of Ghosts"), Vilcabamba, Peru

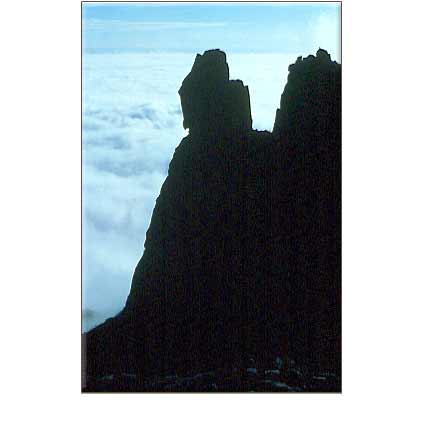

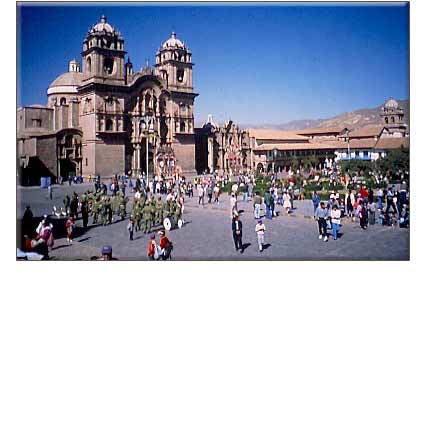

Pico Iccma Ccolla overlooking the valley of Espíritu Pampa ("The Plain of Ghosts"), Vilcabamba, Peru The Plaza de Armas in Cuzco, world-famous capital of the Inca Empire

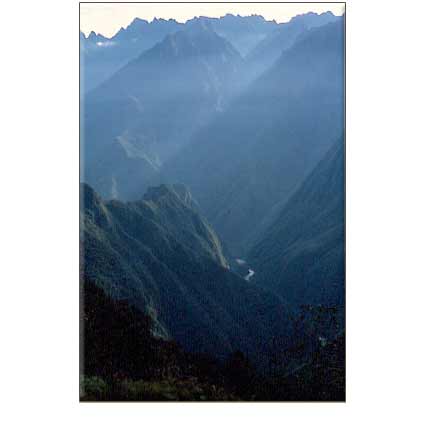

The Plaza de Armas in Cuzco, world-famous capital of the Inca Empire The Grand Canyon of the Urubamba River seen from the Inca Trail en route to Machu Picchu

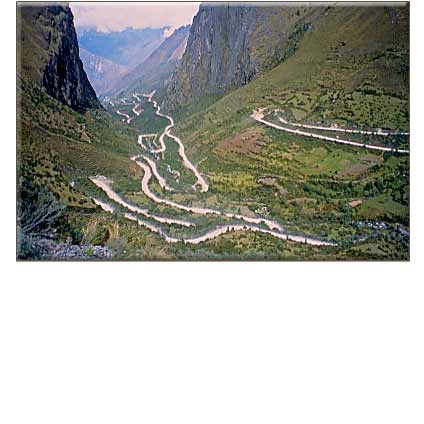

The Grand Canyon of the Urubamba River seen from the Inca Trail en route to Machu Picchu The 14,000-foot Malaga Pass, the only auto route into Vilcabamba, Peru

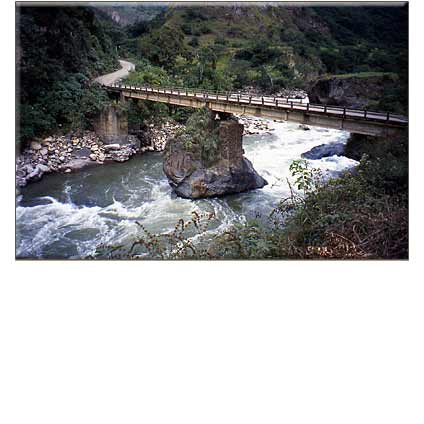

The 14,000-foot Malaga Pass, the only auto route into Vilcabamba, Peru The historic Chuquichaca crossing of the Urubamba River with surviving Inca stonework on the midspan boulder

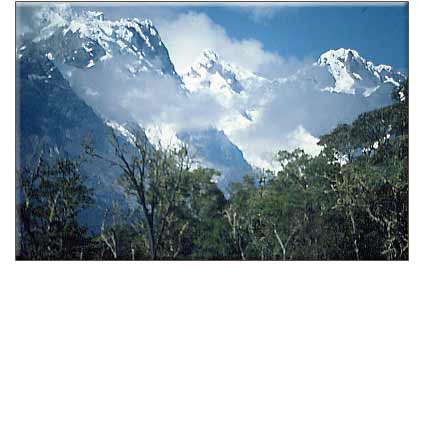

The historic Chuquichaca crossing of the Urubamba River with surviving Inca stonework on the midspan boulder 6000-meter peaks of the Cordillera Vilcabamba rising sheer from the forest

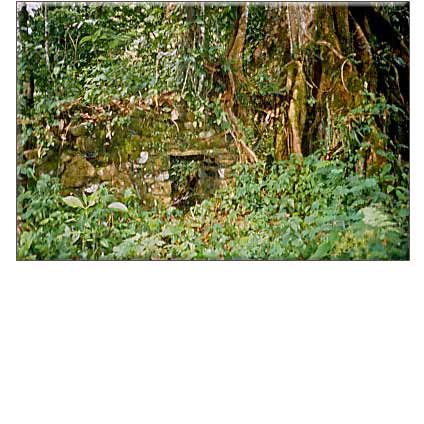

6000-meter peaks of the Cordillera Vilcabamba rising sheer from the forest Typical rain forest en route to Espíritu Pampa

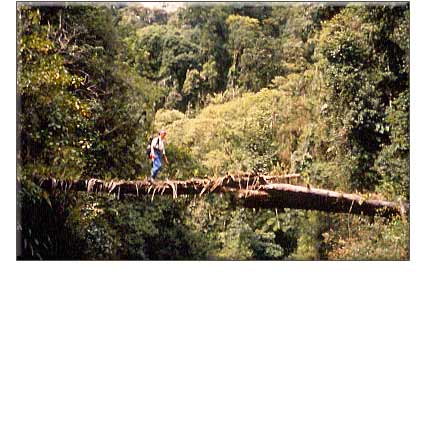

Typical rain forest en route to Espíritu Pampa Nancy Lee crossing a cantilevered pole bridge en route to Espíritu Pampa

Nancy Lee crossing a cantilevered pole bridge en route to Espíritu Pampa The valley of Espíritu Pampa viewed from atop the 1000-meter Inca entrance stairway

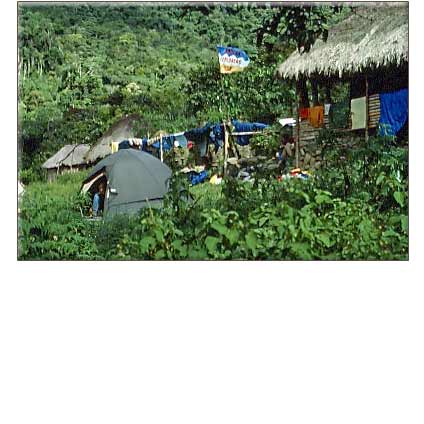

The valley of Espíritu Pampa viewed from atop the 1000-meter Inca entrance stairway Sixpac Manco II camp at Espíritu Pampa, 1984

Sixpac Manco II camp at Espíritu Pampa, 1984 Typical jungle-covered ruins of Vilcabamba The Old, the Incas' final refuge, at Espíritu Pampa

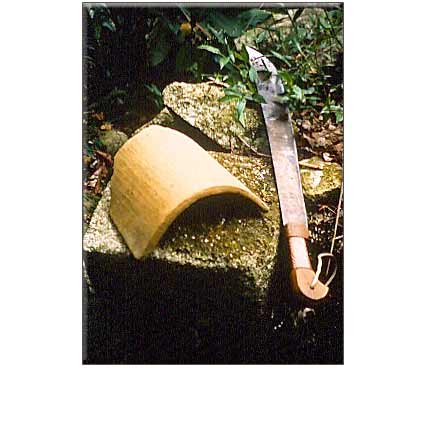

Typical jungle-covered ruins of Vilcabamba The Old, the Incas' final refuge, at Espíritu Pampa Imitation Spanish roof tile and cut stonework in the ruins of Vilcabamba The Old

Imitation Spanish roof tile and cut stonework in the ruins of Vilcabamba The Old Ben Giles with a two-meter boa constrictor encountered in the ruins

Ben Giles with a two-meter boa constrictor encountered in the ruins

Excerpt

Furious that I had missed what might have been my only opportunity, ever, to experience contact with Stone Age people, I grudgingly agreed to start back to camp. It was getting late and we had a long way to go. We re-forded the frigid Chaupimayo further upstream than where we crossed in the morning. Once back on the trail, our route home soon arrived at the Río Yurakmayo, the large tributary of the Chaupimayo Barefoot and I had forded near its mouth two years before [Figure 47]. A high bridge of poles had been thrown across by the campesinos, but it looked as though no one had used or repaired the crossing in weeks, likely another side effect of the season of terrorism. Still, none of us wanted to wade another icy creek, and over we went, one at a time with José in the lead and me in the rear. Just as Ben was about to disappear into the forest on the far side, I stepped out onto the logs and heard a resounding “crack!” In an instant, I found myself hanging from a slippery pole by one hand and clutching my journal in the other. “Ben!” I screamed, “the journal!” and flung it as hard as I could towards the other side just as my hand lost its grip and I dropped into the rapids below.

In a flash, on the way down, I remembered a curious comment Savoy had made months before. Describing how he’d lost everything — wife, family, land — when he had been run out of Peru years ago, he said, “at least I got out with my journals.” At the time, Nancy and I had thought it a strange comment, but now I understood with crystal clarity. The little book I had just thrown away was all I had to show for five long weeks of backbreaking work. Replacing it would be out of the question, at least for another year, and who knew what might happen in a year’s time. Fortunately, I landed in a deep pool and although swept immediately into some boulders, I scrambled out scratched, shivering and shaken, but unhurt. Ben had the book, wet because my throw had fallen short, but he had grabbed it before it was caught by the current. I flopped down on the bank, panting with relief. Later that night, I dried the soaked journal, page by page, over an open fire. To this day it smells of fire smoke and brings back powerful memories of the Plain of Ghosts. At the time, though, and for the second time that afternoon, my heart was racing out of control — and the excitement wasn’t over yet.

The gloomiest part of the trail back to camp was just beyond the stone bridge that was once the entrance to the center of the city. By the time we got there it was nearly dark and visibility was nil. We had been talking about how most snakes were nocturnal and it was best to stay out of the woods at night. José said that was true, especially over in the San Miguel valley where there were lots of “shushupes,” as he called the huge bushmasters that stalked the lower elevations to the north. He had always insisted that serpientes, snakes, were not a problem at Espíritu Pampa and he routinely crashed about in the brush bare-legged in sandals as if to prove it. We had always followed suit, but nervously, since to us ignorant gringos, the country thereabouts looked like snake heaven.

Being in the lead, I turned to warn the others about a rock in the trail just as I moved uneasily to step over it myself. Uneasily, because I didn’t remember anything being there earlier in the day. Then, out of the corner of my eye and in mid-stride, I thought I saw the rock move. As my vision slowly focused in the fading light I recognized the long tail and hind legs of a rat-like animal about 18 inches long disappearing into a grotesquely distended mouth in the midst of a huge mass of writhing, slate gray coils. “Yeeoow!” I yelled and jumped back, my heart once again pounding, seemingly in my own mouth. “What the hell is that?” I barked rhetorically, knowing only too well what it was. We had interrupted a very large snake in the midst of its dinner. José insisted on killing the poor thing even though I was against it once I calmed down. It was, he said, an asp’a — but thankfully, no relation to Cleopatra’s. Rather, it was a fairly beneficial and harmless constrictor, except to 18 inch rats, it seemed. This one was about eight feet long and as big around as a man’s upper arm. Harmless or not, I would have gone into cardiac arrest, I know, if I had ever tangled with one face to face during our countless episodes thrashing about in the bush.

The next day we had to begin the long return trip upriver. We had done all we planned, but there was half a roll of extra-fast film left and I decided to go back into the city alone for a few more shots before breakfast. The low-lying area west of the plaza [Figure 53] was thickest of all and it received so little daylight that even using special film, I had to cut away lots of vines and foliage to get decent pictures. It was a tedious routine because I had to cut and then check the light, cut and check, over and over again. A machete in the jungle is much like an ice axe in the mountains. When needed, it’s needed badly, but at all other times it is just in the way. To free both hands for the light meter, I got into the careless habit of sticking mine in the ground, blade first, but it wasn’t smart. Anything left loose in the jungle blends quickly into the foliage and is easily lost. Still, I figured a few final shots wouldn’t make any difference. Not so. I had just snapped my very last picture when I got the feeling something was wrong. It took a minute to realize the machete was missing. Not only did I need it to get out of there, but, I belatedly recalled, it was special. I traded it from a Negrito pygmy in the Philippines when I was there with the Marines back in the 1960s. Unlike the Collins & Co. el cheapos, available for a buck or two in every mercado in Latin America, my machete was forged from an old World War II jeep spring and had a hand-carved handle made from water buffalo horn. Over the years, I came to think of it as an old and valued friend. I looked everywhere, but couldn’t find it. Frantic, I went back over every step I had taken since I last remembered having it in my hand, but it was gone. Perhaps it was Tupac Amaru’s way of telling me, “Go home, gringo! There’s nothing more for you to do here.”

Empty-handed, I turned back towards camp, discouraged and thoroughly depressed. Standing there motionless in the forest watching me were the Machiguengas. From Ben’s description, it was the same outfit they had seen the day before, except now there were five. Sometime in the night, the woman had given birth and the tiny baby was now at her enormous breast. She held it with one arm while still carrying all the group’s possessions with the other. The men both had chonta palm bows half again taller than they were and an assortment of meter-long arrows. Some were barbed for fishing and others had blunt tips, I guessed for stunning birds. Wrapped twice around the older man’s waist and tied at one side was the slate gray skin of our asp’a, apparently eaten for dinner. José had flung it off into the forest. How had they found it? And what about the rat? Had they had him for breakfast, I wondered? The thought of it gave new meaning to the phrase “hunter-gatherer.”

All five were nearly naked, none wearing more than a few filthy rags. The only exception was the grimy red, white and blue wool “US SKI TEAM” hat worn incongruously by the younger man. We grinned at each other and shook hands all around in limp, Andean fashion, but they seemed to understand little Spanish. Besides Machi, they spoke Quechua like their highland cousins. Either way, I was pretty much out of the loop. Still, by eye contact, gestures, and an occasional word or phrase, we chatted as best we could. They nodded tentative agreement with José’s story about ruins beyond the mountains. Nevertheless, there was little doubt we were separated by much more than a language barrier. In fact, we might as well have lived on different planets, for what little we had in common. As if to underscore the point, the early Aero Peru flight from Lima passed high overhead on final approach into Cuzco, only a few minutes away by jet. We all looked up and watched it, silently lost in our own thoughts. What on earth did they make of that, I wondered? I tried asking, but they just shrugged and pointed to the sky, grinning at one another.

On that note, the trip effectively ended. The plane reminded me how much I wanted to get the hell out of there and back to the world of cold beers, clean sheets and sweet, café cortado in the morning.

Vincent R. Lee

Sixpac Manco Publications

P.O. Box 174

Cortez, CO 81321 USA

(970) 564-8270

Wikipedia page