BUILDING BIG WITH NEXT TO NOTHING

Did extraterrestrial aliens help our ancient ancestors create the megalithic wonders of antiquity? Of course not! Those marvels were accomplished by clever, industrious people just like us. Read on and learn how they could have done it.

Building BIG With Next To Nothing

Imagining how ancient builders accomplished so much with so little has fascinated me ever since my boyhood days, playing with blocks and Lincoln logs, trying to mimic the images of former worlds that I saw in National Geographic magazine. Thousands of workers were shown on long ropes hauling huge blocks over log rollers on giant timber sleds. Treadmills lifted stones high into the air with wooden cranes while masons cut intricate shapes with simple hammers and chisels. Was that really how people thousands of years ago built the Seven Wonders of the World? I longed to find out.

Years later, during a long career in residential architecture, I came to understand how complicated even modest building projects actually are, and how clever even modern-day workers are at solving difficult problems. My appreciation for the master builders of old grew all the more, considering how little they had of the technology we take for granted today. Over time, this grew into a passion to visit their monuments and see for myself what clues they offered to the trained eye. By and large, they left us no records of their methods, leaving little choice but to reverse-engineer their work and field-test the many ideas suggested there Another career, this time in archaeology, provided me the opportunity to do just that.

This volume is a collection of monographs describing a wide array of studies and experiments in ancient building methods. They are the result of more than thirty years of fieldwork and travel to many of the ancient world’s most fascinating and astounding sites. Two of the projects described were featured on NOVA television episodes. Others have been aired on the History and Discovery channels. Several of these and others have been published in various peer-reviewed journals. This should not be taken as proof that the problems addressed have been “solved.” Our results do strongly suggest, however, that the ancients were no less imaginative than we are, and worked their magic with little more than simple tools, well-organized manpower and an abundance of focused human intelligence.

Take a look inside this publication

Table of Contents

The Lost Half of Inca Architecture

The Lost Half of Inca Architecture examines the pole and thatch construction used by the Andean Incas to roof their magnificently crafted stone structures. A single example of an original Inca roof survived well into the 19th century and suggested that that their thatch-work was far more elaborate than anyone had expected. Based on descriptions of this structure, plus eye-witness reports in the 16th century Spanish chronicles and analysis of roof attachment points still evident in the masonry of well preserved Inca ruins, this “lost half” of Inca architecture is reconstructed and shown to be just as impressive as the world-renowned stonework it once crowned.

Design by Numbers sets out to discover how the Incas of Peru designed and managed construction of the highly organized and classically geometrical building complexes for which they are justly famous. Less well known is that they accomplished it all without any of the tools nowadays considered essential to the process: scaled drawings, numerical notations, written instructions, and universal units of measure. Absent all of these, they created Machu Picchu and a thousand other architectural wonders, and did it well, but how? Design “by numbers” may have been their secret.

The Sisyphus Project was conceived during filming of a NOVA television production on Easter Island. The subject was how the islanders centuries ago erected the huge moai statues that once ringed the tiny island, gazing inland from their seacoast ahu platforms. Like all researchers before them, the NOVA crew enlisted a large gang of locals to drag their faux moai across the island. But there was a problem. Once the front rank of pullers reached the ahu at water’s edge, there was no way to move the statue further. The solution, successfully tested by the Sisyphus Project, solved a universal puzzle: how to move a huge stone into a constricted place, with no space for large battalions of workers to drag it into place.

Reconstructing the Great Hall at Inkallacta

Reconstructing the Great Hall at Inkallacta, Bolivia, has long troubled researchers due to a tiny detail on the still-standing eastern gable wall hardly noticeable to casual observers. The Great Hall is the largest standing example of an Inca kallanka. All of their large sites had one or more to accommodate big indoor gatherings. Here, the 26 x 78 meter covered area called for an enormous thatched roof, but the steep slope suggested by the intact southeast corner of the building suggested a truly monumental structure, 20 meters high. Was the original thatch-work really that tall, and in any case how was such a large roof supported? The answers turned up once the hall’s other end was cleared of brush and we found that the fallen west gable wall retained much of its original shape.

Ancient Moonshots begins in Part I with a brief primer on building with large stones, plus a description of the tools available to archaic stonemasons and the forces at play in their work. This is followed by a summary of proven hand methods for manipulating giant blocks. The title comes from the fact that the most daunting of the ancient world’s wonders were their builders’ equivalent of our space program, and grew from much the same human desire to push the envelope and accomplish the “impossible.” Part II of Ancient Moonshots explores four such projects, left unfinished by their builders and applies the methods described in Part I to finishing the job.

Sacsawaman, An Inca Masterwork

Sacsawaman, An Inca Masterwork crowns a mountaintop overlooking Cuzco, the magnificent capital of the Inca Empire. Begun sometime in the 15th century, it was still under construction upon arrival of the Spaniards in the 16th. They thought it a fortress due to its resemblance to a European castle, and were especially dazzled by the three stone-faced terraces that protected the fort’s northern flanks. More than 400 meters long and 20 meters high, these walls were built using thousands of giant boulders, some weighing over a hundred tons, all perfectly fitted in the classically polygonal Incan style. How was it done? Here is proposed an entirely new and unexpected method, tried and proven in two televised field tests.

El Gigante, Awakening the Giant

El Gigante, Awakening the Giant, describes a series of methods for completing the erection of by far the largest moai on Easter Island. Still in the quarry, the “Giant” is fully formed, but has yet to be undercut and detached from bedrock to begin its journey across the island to a seacoast platform, or ahu. Over 20 meters tall, and weighing in at more than 270 tons, it is twice the size and more than three times the weight of the largest moai ever erected by the ancient islanders. New ideas are proposed for freeing the statue from its bed, lowering it down the debris slope beneath the quarry cliffs and transporting it to its ahu. In keeping with local tradition, El Gigante makes the final journey standing erect, and the statue is finally crowned with a 40-ton pukao, or hat, again using totally new and unexpected methods.

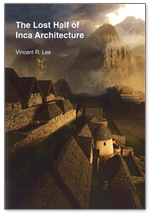

The Unfinished Obelisk lies abandoned in Egypt’s famous granite quarry at Aswan, near the First Cataract of the Nile. Nearly finished, it developed a fatal crack before being undercut and extracted from its deep bay in the virgin rock. Completed, it would have weighed nearly 1200 tons and stood 42 meters tall. It was the largest obelisk ever conceived and would have been one of the largest megaliths ever carved and moved by man. Here, we ignore the flaw that derailed the original project and pick up where the Egyptians left off. Detailed methods are suggested for raising the huge monument from its bay, moving it to a pair of giant barges for transport downriver to Thebes, and erection there by means of a new and more efficient method than that currently favored by many researchers.

Baalbek’s Trilithon: An Enigma

Baalbek’s Trilithon is the world’s greatest megalithic enigma, but the three gigantic building blocks known by that name are, literally, just the tip of the iceberg. Nearly hidden beneath the spectacular ruins of Lebanon’s Temple of Jupiter-Baal, the largest ever built by the Romans, are 24 400-ton blocks found supporting the 900-ton Trilithon stones. Awaiting transport in the nearby limestone quarry lies the 1200-ton Stone of the South, once thought to be the largest in the world. Not so. Just across the modern highway that bisects the quarry, a small exposed corner was found to be part of an even larger, 1500-ton, megalith once the silt of centuries was cleared away. Then, in 2014, a German expedition excavating beneath the Stone of the South discovered a maxilith, estimated to weigh 1650 tons! Conventional wisdom holds that this was all Roman work, abandoned for some unknown reason in favor of the thousands of much smaller stones used in the finished temple. Nothing could be further from the truth. Despite some tantalizing clues, we have no idea who built the Trilithon, when it was done or for what purpose.