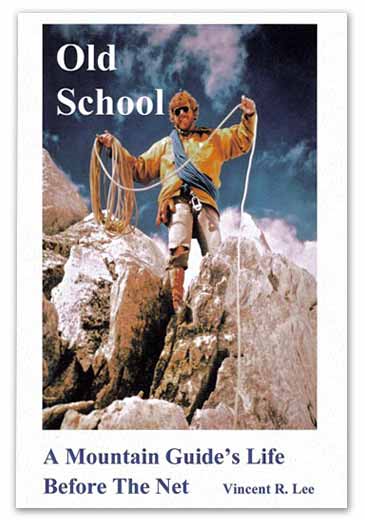

OLD SCHOOL: A Mountain Guide’s Life Before the Net

This is a story of a mountain guide’s life before we were all deported to the tiny planet Cyberon, where Connectivity is King and getting away and back to the Earth a forgotten joy

OLD SCHOOL: A Mountain Guide’s Life Before the Net

It was the Golden Age of backcountry mountaineering and Vincent Lee was lucky enough to be there. Forty years he wandered the high country, thirty as an instructor and guide, mostly with young beginners.

The ranges were wild and empty. The digital genie was still in its bottle. No net, GPS, sat or cel phones. Packs were big. Food was awful. Tired, scared, hungry, bug-bitten, filthy, wet and miserable Lee and his clients were, but they felt like giants, latter-day “mountain men,” roaming the wilderness, avoiding trails, fording rivers, camping wherever they wanted, climbing whatever they liked, dealing with the Earth on its own terms.

The whole idea was to disconnect, get out, up and away and for a few brief, shining moments be free! How rare today the freedom they so easily found then.

Take a look inside this publication

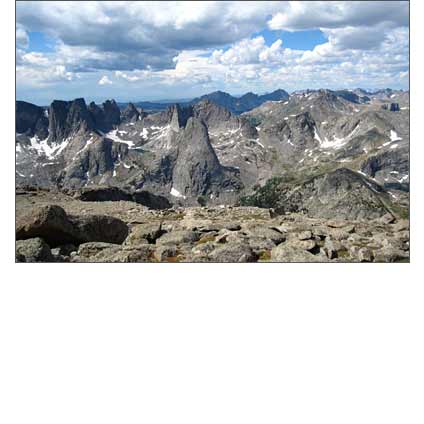

Cirque of the Towers, Wind River Range, Wyoming, Pingora Tower @ center.

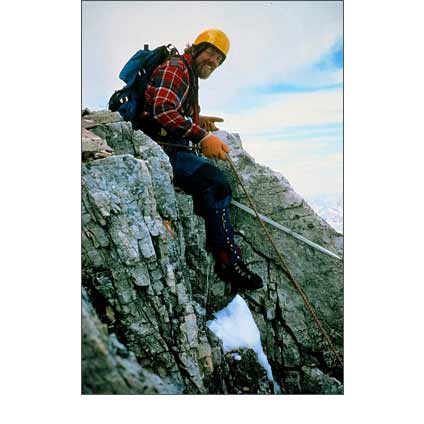

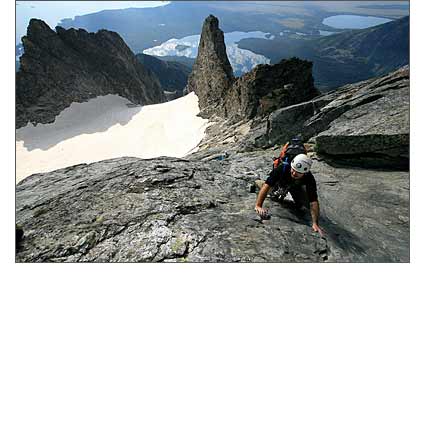

Cirque of the Towers, Wind River Range, Wyoming, Pingora Tower @ center. The author belaying near the summit of Mt. Assiniboin, Canadian Rockies.

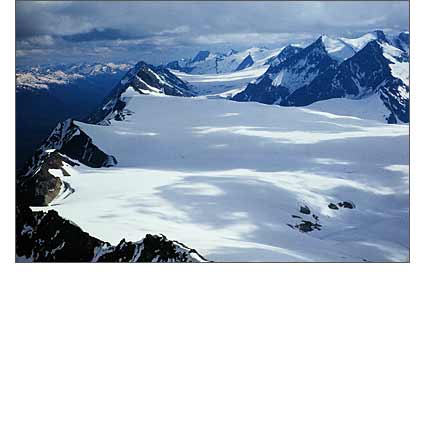

The author belaying near the summit of Mt. Assiniboin, Canadian Rockies. Canada's Illecillewaet Icefield from atop Mt. Sir Donald, Selkirk Mountains, Canada.

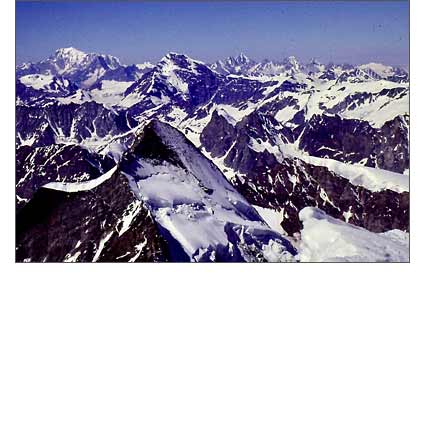

Canada's Illecillewaet Icefield from atop Mt. Sir Donald, Selkirk Mountains, Canada. View from atop the Matterhorn toward Mont Blanc (upper left), Swiss / French Alps.

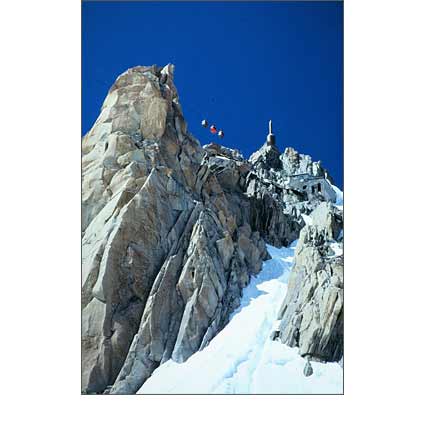

View from atop the Matterhorn toward Mont Blanc (upper left), Swiss / French Alps. Aguille du Midi teleferique, Chamonix, France, with cars nearing the summit.

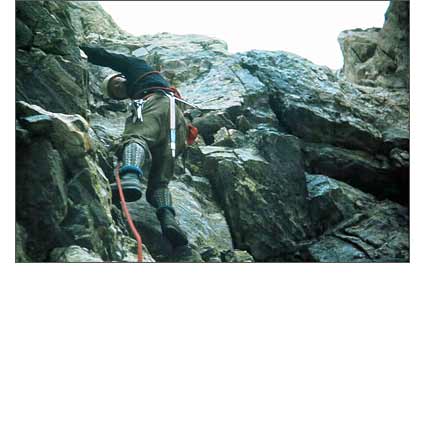

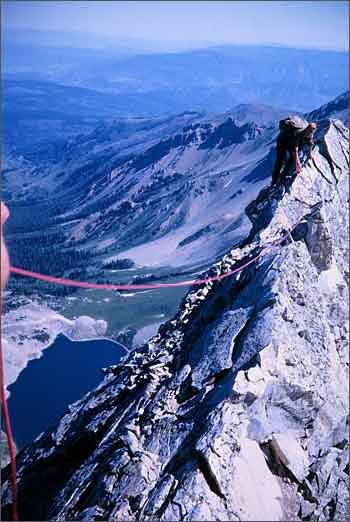

Aguille du Midi teleferique, Chamonix, France, with cars nearing the summit. The author on the Grand Teton's Petzoldt Ridge route, Wyoming.

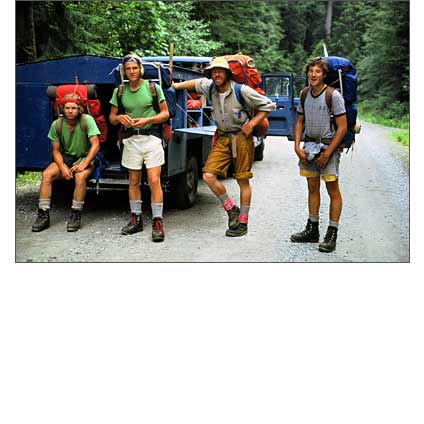

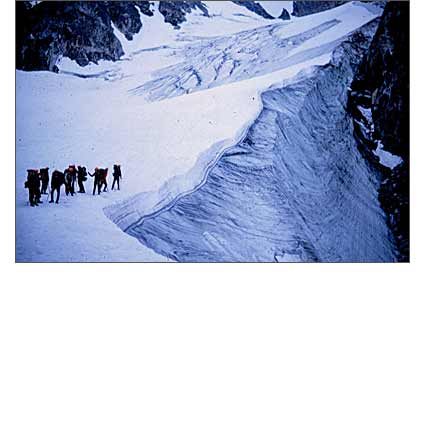

The author on the Grand Teton's Petzoldt Ridge route, Wyoming. Clients following 2-week crossing of Washington's North Cascades, author with hat.

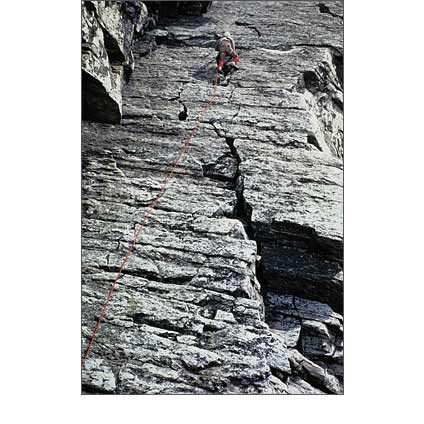

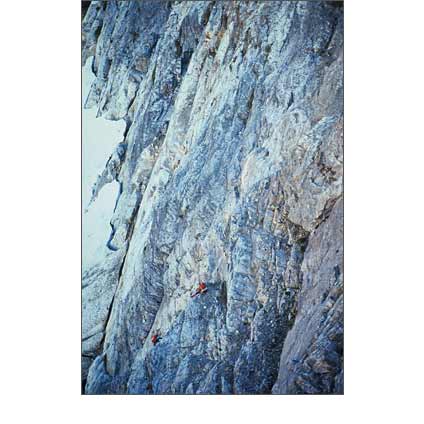

Clients following 2-week crossing of Washington's North Cascades, author with hat. Author leading on perfect quartzite wall in Selkirk Mountains, Canada.

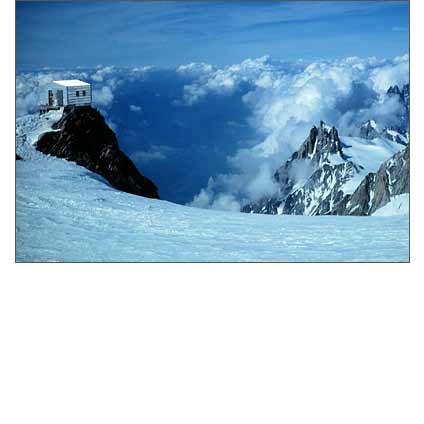

Author leading on perfect quartzite wall in Selkirk Mountains, Canada. The Grands Mulets refugio, midway down the Bossons Glacier, with the Aguille du Midi and Vallee Blanche, Mont Blanc, French Alps.

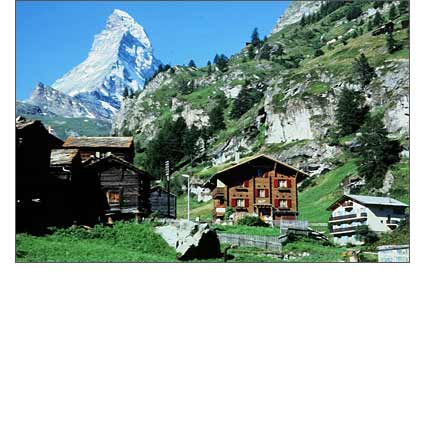

The Grands Mulets refugio, midway down the Bossons Glacier, with the Aguille du Midi and Vallee Blanche, Mont Blanc, French Alps. The Matterhorn from the farms above Zermatt, Swiss Alps.

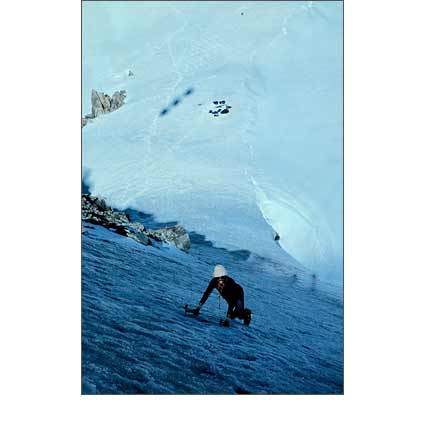

The Matterhorn from the farms above Zermatt, Swiss Alps. Ice Climbing on the Tour Ronde, Valle Blanche, Chamonix Aguilles, French Alps, with our camp below.

Ice Climbing on the Tour Ronde, Valle Blanche, Chamonix Aguilles, French Alps, with our camp below. View down the CMC face of Mount Moran, Wyoming Tetons, with West Horn and Falling Ice Glacier below.

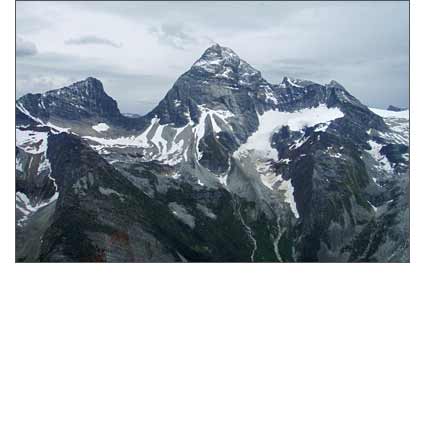

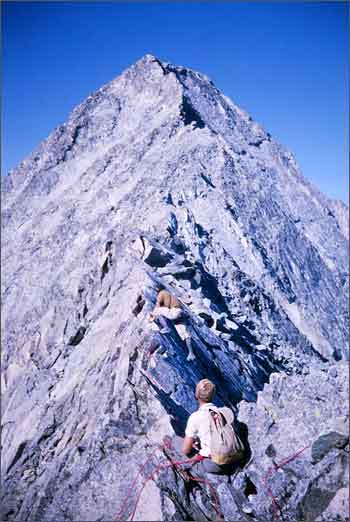

View down the CMC face of Mount Moran, Wyoming Tetons, with West Horn and Falling Ice Glacier below. Mt. Sir Donald, Selkirk Mountains, Canada, famed NW Arrête right of "U" notch.

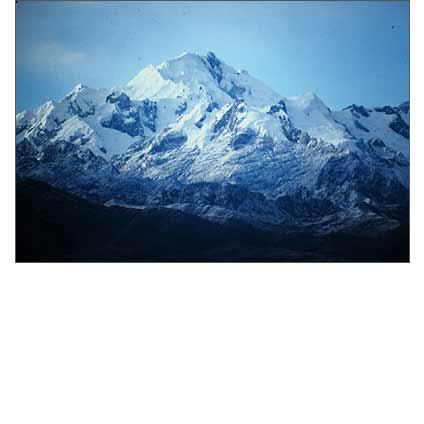

Mt. Sir Donald, Selkirk Mountains, Canada, famed NW Arrête right of "U" notch. Nevado Pumasillo (the Puma's claw), 6090-meter giant, Cordillera Vilcabamba, Peru.

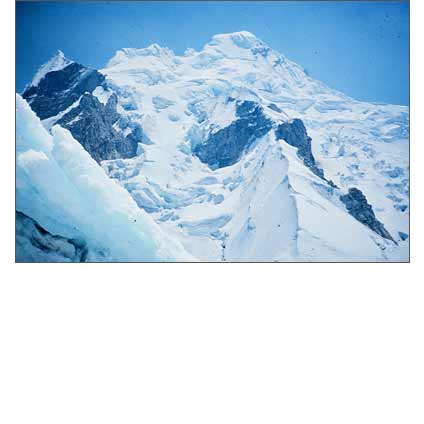

Nevado Pumasillo (the Puma's claw), 6090-meter giant, Cordillera Vilcabamba, Peru. Author's route on 6000-meter Cerro Lasonayoc, Cordillera Vilcabamba, Peru.

Author's route on 6000-meter Cerro Lasonayoc, Cordillera Vilcabamba, Peru. Backpack route up the Deville Icefield headwall from Glacier Circle, Selkirk Mountains, Canada.

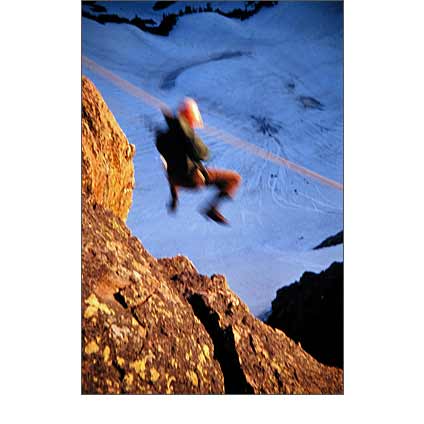

Backpack route up the Deville Icefield headwall from Glacier Circle, Selkirk Mountains, Canada. Tyrolean Traverse training, Teton Range, Wyoming.

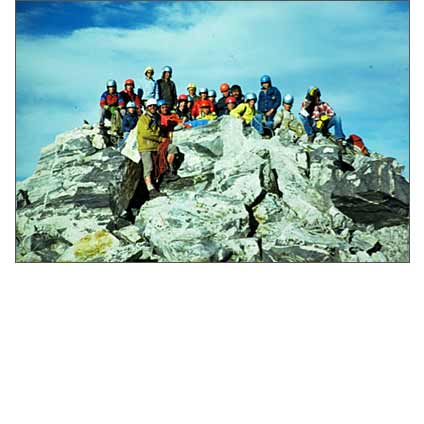

Tyrolean Traverse training, Teton Range, Wyoming. Troop 40, BSA, Wilson, Wyoming, on the summit of the Grand Teton.

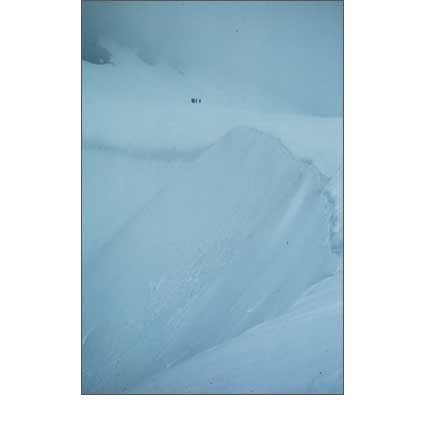

Troop 40, BSA, Wilson, Wyoming, on the summit of the Grand Teton. At the snowy Sasquatch Pass, British Columbia Coast Mountains, Canada.

At the snowy Sasquatch Pass, British Columbia Coast Mountains, Canada. On Dinwoody Glacier below Gannett Peak, Wyoming's highest, Wind River Range.

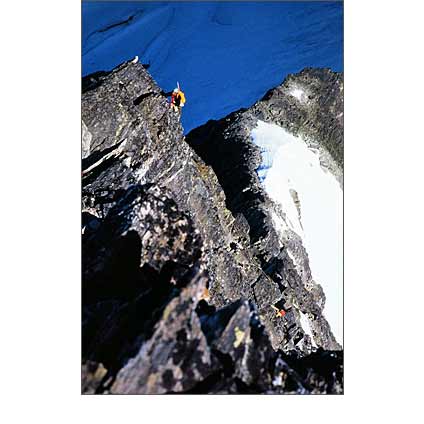

On Dinwoody Glacier below Gannett Peak, Wyoming's highest, Wind River Range. On Mt. Sir Donald’s incredible NW Arrête, Selkirk Mountains, Canada.

On Mt. Sir Donald’s incredible NW Arrête, Selkirk Mountains, Canada.

Excerpt

Paul (Petzoldt, @ Colorado Outward Bound in 1964) thought every student should climb a ‘big’ mountain before leaving camp. He arranged their schedules so that sometime in the last half of July, they would climb nearby 14,137-foot Capitol Peak by its justly famous Northeast Knife-edge.

High Camp We’d been humping huge loads all day and finally found a flat spot big enough for five or six tents. It was somewhere around 13,000 feet, so it was all rocks, with a nearby snow bank for water. Also a short scramble from where we’d be roping up, it would save climbing time once the students began to show up. That was Paul’s plan: the four of us would stay up there and meet the patrols as they came by. We’d divide them into threes and each of us would take a team up to the summit, then bring them down and turn them loose to continue on their way. The “challenge” was just beyond camp, an easy, but razor sharp section of the ridge-crest with horrendous drops on both sides. For us, the big problem was protection, horizontal traverses being notoriously difficult to safeguard. The rest of the climb to the summit was easy scrambling, so we’d earn our pay each day crossing and re-crossing the knife-edge. At least, that’s what we thought.

The appropriately-named Knife-edge.

Dead tired, we cooked a quick dinner and turned in, even though there was still a bit of daylight left. No sooner had we dozed off, but a bunch of noise outside the tents woke us up and got me out to see what the hell was going on. It turned out to be our first patrol group, also tired but excited by the huge summit pyramid looming just beyond camp. I told their patrol leader to quietly find tent-sites and settle in for the night. Since we were all so tired, I said we could sleep in a bit in the morning and get up around eight. “Wow! Is the climb that short?,” he asked. “The weather’s good and we’ve got all day, don’t we?,” I replied. “No way,” he said. They had to be off to their next “challenge” by noon. Oh man, just what we needed! A crack-o-dawn start the first day! “OK,” I said. “Up at four and back by noon,” and stumbled back to bed.

Four o’clock came minutes later, or so it seemed. We all climbed out of bed, ate a quick cold breakfast of gorp, granola and such, figuring we’d cook up a real meal when we got back. We divided into teams and roped up in camp so I could see if they all knew what they were doing. That turned out to be a good idea, since the patrols varied a lot in their skill levels. These guys were pretty good, so off we went. We had three teams of four and one of three, which turned out to be fairly typical. At the knife-edge a goodly amount of the previous night’s enthusiasm evaporated. Suddenly, they were looking straight down hundreds of feet to the boulders and meadows below. This void fell away on both sides of a crest at places sharp enough to cut yourself on. Yikes! How were they going to get across? Each of us leaders in turn went out bit less than half a rope length, maybe 50 feet, leaving protection along the way for those behind. Then the second man would come out, change positions with us, and bring out the third man while we went on without belays to speed things up. I forget how many leads were required, but it was several to get everyone over. Not until our last man started out, could the next leader begin. If you’re beginning to get the idea that this took awhile, you’re right, and we had to do it all over again to get everyone home.

Capitol Peak viewed across the Northeast Knife-edge.

One of Petzoldt’s favorite lessons was to “take care of yourself first! Make damned sure you can’t get pulled off the mountain, no matter what!” The idea was that if everyone did that, no one would fall off the mountain. In practice, it means you should either be belayed or anchored at all times, never, ever standing around on exposed ground unsecured with a big pile of loose rope at your feet. It sounds easy, but up on a tiny ledge above a big drop, rope handling can be tricky. Changing belays offers lots of opportunities for mistakes and that’s what the kids were doing over and over again. We kept an eye on them as best we could, but mainly had to trust their training. I thought of the Marines at Pickel Meadows that we drilled until they were as good at it as we were, and wished we’d had the time to do the same with these guys. Finally, we were over without any incidents and headed for the summit. The pyramid, so imposing from camp, was actually an easy scramble, so we unroped and picked our way carefully up the boulders. Even this took time, since everything was loose and we had lots of people both above and below us. Nevertheless, we arrived at the summit around 8:30, all the boys excited about the big climb. They all shook hands and congratulated one another. I pretended to join in, but preferred to save the celebration until safely back at camp.

Like any good guide, I was instead thinking about getting everyone off the thing in one piece. It’s an old and true axiom that most accidents happen on the way down, while everyone’s tired and careless, thinking the hard part’s over. Not in this case. We all had to get down a gigantic pile of loose rocks and back across the bottleneck beyond to get home, and doing it safely wasn’t going to be easy. At least we didn’t have to worry about weather. Afternoon clouds were beginning to form, but we’d be off the climb before they posed a threat. The descent seemed to take forever, though, and I started worrying about the noon deadline I’d agreed to. Worrying is something guides do a lot, and this particular “challenge” offered plenty of opportunities. We arrived at the knife-edge at about ten, with what seemed ample time to get everyone across. Thankfully, everything went well again and the last team got back to camp a little before noon. Being teenagers, they still had lots of energy, and breaking camp without a rest was no problem. They were off and on their way to their next “challenge” minutes later.

We four guides, on the other hand, were exhausted, hungry and in need of some serious down time. We had just finished cooking up lunch, however, when we were surprised to see another patrol approaching camp. “Why so early?” I asked the patrol leader once he was in camp. “You’re not gonna believe this,” he said, knowing full well what it meant to us, “But we have to be on the road again first thing tomorrow morning to get to our next “challenge.” “Holy shit!”, I said, “Drop your packs, get out your climbing gear and be ready to go in five minutes!” Unbelievable! We were scheduled to do the climb twice in one day. I hoped it was some sort of glitch, but somehow knew otherwise. Meanwhile, off we went with those early morning clouds now filling the sky, heavy and gray. There’s no need to describe the climb. It was much like the one in the morning, but with weather a constant threat and something else to worry about. Rain wouldn’t be a big deal, but at that altitude it might snow, and that would be trouble. Most threatening of all was lightning, of course, and a worse place to be or route to be climbing couldn’t be imagined. The summit, the knife-edge, even camp was exposed. It being early July, we had daylight until almost 10 PM, and fortunately so, since we dragged into camp at about 9:30, the boys tired, but us guides completely done in. All was well with one exception, the next patrol, the one for tomorrow morning’s climb, was already camped and sound asleep.

It wasn’t a glitch. Paul had us scheduled for two climbs a day until every patrol had climbed Capitol Peak. I have no idea how we pulled it off, but without very much of either food or sleep, we got everyone across the knife-edge and up to the summit and back without accident. There were slips, of course, caught before they’d fallen very far, and freeze-ups, who needed coaxing across the scary part, but nothing serious. Afternoon showers got us wet and cold a few times, but the lightning always stayed away. We four, however, became so familiar with the holds, that to speed things up, we scampered back and forth across the knife-edge, un-roped, as if we were on flat ground. It saved time, but wasn’t smart. Another old truism is that good climbers often come to ruin on easy ground, and that would surely have been the case if any of us had fallen. I don’t remember how many days we were up there, but it was at least a week, so we probably did the route about fifteen times. I do remember how it all ended, with the four of us musketeers drunk in an Aspen bar. Paul had to send a truck around the mountain to bring us home.